I used to think that online education held great possibility for the democratization of access to information, and for the provision of schooling “anytime, anywhere” to learners who — for a host of complex reasons — needed flexibility.

Thinking back to “the before times” I used to love teaching online. I loved the way that the online space focused me on the immediate needs of the students I was serving. I had the feeling that even though we weren’t all working in the same physical space, I did share a meaningful psychological space with my students that we co-constructed iteratively through emails, chats, lessons, and rounds of feedback on assignments. The creative designer in me loved figuring out how to turn sterile, technically constrained learning management systems into inviting, predictable learning environments that felt humanizing and supportive of my students’ various learning needs — or at least I always hoped that this was how these spaces felt to the thousands of (mostly teen and adult) learners I have served in my online courses. Heck, I even won awards, with colleagues, for our online course designs in higher education.

So, when the world “pivoted” online at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, I felt ready to share what I had learned and even studied for a little while during a one-year stint as Director of Graduate Certificate Programs in Online Teaching and Learning at the Michigan State University College of Education.

In response to a need in our Faculty of Education at the University of Ottawa, I used what I knew to write an openly accessible intro-to-online teaching course for preservice teachers with my colleague, Hugh Kellam. The CBC called me a few times to comment publicly on the merits and the drawbacks of online instruction and in those conversations I stuck to the evidence that existed at the time and tried to offer a balanced view. Nobody had ever lived through a global pandemic before. The best evidence on online teaching and learning that we had at the start of all this suggested that (a) when designed with accessibility, empathy and an ethic of care as primary drivers, and (b) when adequate professional supports are put in place for students, educators and families, it could be as effective as in-class instruction for enough learners that it might be okay as a stop-gap measure while the public health officials and vaccine researchers figured out how to get this virus under control.

Around the same time, I joined up with a group of esteemed colleagues to develop and publish the CHENINE charter on the equitable use of tech in systems of schooling. In our 10-point charter, we emphasize the fundamental importance of in-person instruction for learners in physical school buildings, but recognize that digital technologies do have their place when used judiciously and strategically to offer unique and evidence-informed value to learners. I also co-authored a report in response to a provincial RFP with some of these colleagues in which we offered evidence-informed recommendations for how to design equitable, accessible emergency remote instruction for students with identified learning needs.

But, as we enter this moment in Ontario — the one nearly two years into the COVID-19 pandemic when our kids are being asked to do two more weeks of emergency remote schooling, starting tomorrow, with absolutely no assurances that there is a plan beyond January 17th for a return to in-person instruction — the report we submitted for review last March has not been published anywhere that I have seen, and I can’t legally share our draft publicly. I believed that this work, added to the research and advocacy work by experts across healthcare and education sectors that has clearly named the harms of remote learning, and called for in-person schooling to be considered essential (see reports here, here and here) would make a difference. As the parent of two school-aged daughters with learning exceptionalities myself, I can’t decide whether to feel heartbroken or furious.

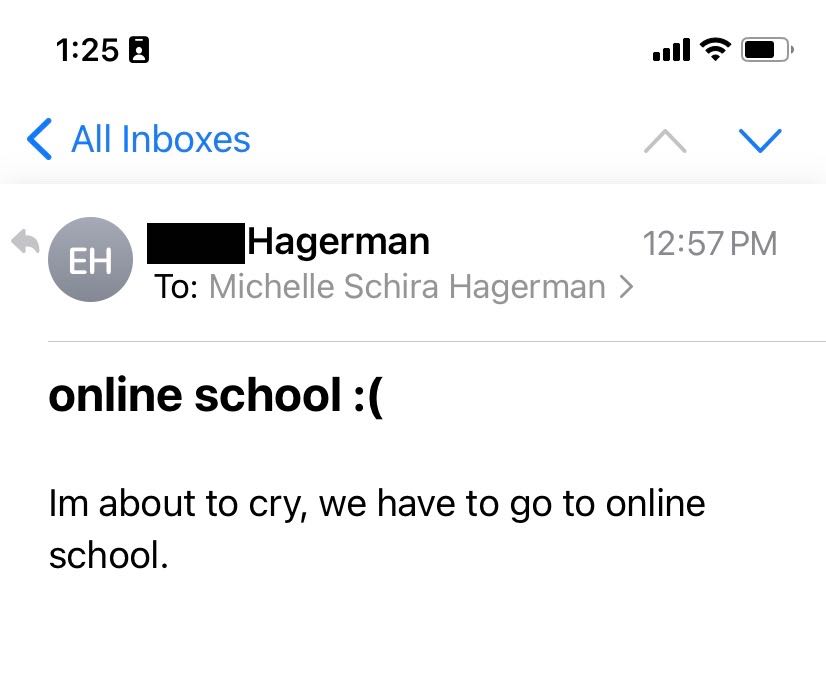

Yesterday, as I worked in my office on a paper highlighting the digital inequalities that continue to impact rural youth in Ontario because they still can’t get reliable high-speed internet, my 11 year-old sent me an email. “Im (sic) almost crying,” she wrote. “we have to go to online school”. So it’s back to trying to prevent my kids from completely collapsing again. And I write this knowing that my white, settler, middle-class family living in the national capital region of this country is wildly, wildly privileged in comparison to many families who have lost their jobs (we haven’t), lost family members to the virus (we haven’t), or may be struggling, among other things to even keep safe, stable housing (with a high-speed Internet connection) from which their kids can join into online school (we are not). This article by Katrina Onstad is a must-read for anyone wondering what remote learning has been like for many families in Toronto.

As an educator with 25 years experience, I knew that remote instruction at the population level could never work for every learner attending school in this province, but I regret suggesting that it could be a temporary solution during crisis in this province. It has fallen so far short of my expectations for what was possible.

And I never anticipated the pervasive harms — outlined in a 22-page open letter to the Premier by more than 500 Ontario Doctors — that would come to so many children, teens and their teachers because of the removal of in-person connections, routines and access to in-person educational experiences for so long. I also never anticipated the impacts of remote instruction on mothers who have most often shouldered the responsibilities of homeschooling their kids. Maybe I was naïve and a little too much of a techno-optimist? Maybe I naïvely trusted that professional learning and infrastructure supports would be provided to front-line educators? Whatever I overlooked, I see the world as it is a little more clearly now.

Even if there were data to support a temporary move to remote instruction, and even if it is true that some students continue to succeed, or do better, despite all of the change that has come at them (and their teachers), the cost of remote instruction to other learners has been far, far too great. Too many kids have lost too much. We know this now. Too many educators have been asked to give far too much of themselves without adequate supports. We know this too. Everyone is burnt out. And it is not right.

There has to be a better way to do schooling than this as we try to work our way out of this pandemic time.

Can we increase and prioritize vaccination rates significantly for 5-11 year-olds, boosters for older students, and for all education workers and staff in schools? Doctors and public health officials repeatedly emphasize that vaccination is the single best thing that we can all do to reduce the impacts of the virus.

As outlined in this evidence brief, many countries are using Test to Stay (TTS) strategies to control the spread of the virus in schools and reduce days missed because of mandatory quarantine when there are cases in schools. The Ontario doctors who penned that 22-page open letter recommend this strategy to reduce blanket closures across the province that are not warranted for all regions. Evidence does suggest that test-to-stay can help kids remain in physical school where they can access the education and the supports they need while regularly testing for infection. Why hasn’t this strategy been mobilized fully in Ontario? There was a moment when it seemed to get started this fall…but then the tests never arrived? Am I right? I haven’t been able to find any study results of the TTS strategy as implemented in Ontario. Does anyone have evidence for why this strategy hasn’t yet been fully implemented?

In the UK, testing measures seem to be the priority so that even amid dramatic increases in daily case counts, schools are remaining open to in-person instruction, as possible, because as Education Secretary Zahawi noted, they learned a “painful lesson” during previous school closures.

I’ve learned a painful lesson too. In the face of evidence that could protect the mental and the physical health of children and teens, the Ontario government has continually disregarded their needs.

For the record, if I don’t respond to your email or meet a deadline over the next two weeks (or month…) please send a follow-up complaint to the team down at Queen’s Park handling emergency remote instruction policies. I’ll be at home, trying to prevent the tenuous threads of mental wellness that my daughters had worked so hard to weave back together this fall….from unravelling.