I’ve decided to begin posting my responses to my colleagues on my blog, in case there are others who could benefit from these thoughts.

I also welcome input from others who could inform answers to these questions!

Here’s the first question.

“I have a question from our Foreign language department chair. Have you found any research on the advantages of reading/writing online vs. reading print (and writing by hand). These teachers feel that in their field the writing by hand is so crucial to learning the language. Thank you if you know of any research specific to learning languages and online vs print reading/writing.”

Here’s how I responded:

In response to your question, here are my thoughts. I do have some research to share — but first, a synthesis of my understanding that could inform your colleagues’ thinking.

1) Language learning is a complex socio-cognitive process that requires vast and varied opportunities for both comprehensible input, but also output. Work by second language scholars such as Stephen Krashen, Merrill Swain and Sharon Lapkin has told us that input and output are essential. And it makes sense, doesn’t it? Opportunities to receive and understand language, but also opportunities to produce language and communicate ideas are obviously essential for the learning of any language. Moreover, the input and the output must take many forms — oral language (input and output) and written language (input and output). Plus, we know that for our students to become confident, fluent communicators, they need access to multiple types of input and output that serve a range of rhetorical purposes and force an understanding of a range of audiences. So, students need to read texts that inform, persuade, describe, narrate etc. and also create these texts. In the 21st century, this needs to occur in digital contexts too. This is because we know that the structures of online texts differ, and that the skills required to produce digital texts for a range of purposes and audiences are different than those acquired through print-based or even face-to-face exchanges. If your colleagues are worried about the digital world taking over — do assure them that traditional, print-based contexts for input and output matter a LOT. Learning to read, write and communicate in the “traditional” ways is as important as ever — and even, perhaps foundational for the development of digital literacies skills. However, it’s my view that to deny students opportunities and access to digital composition is also to deny them opportunities to use language for a variety of purposes and in a variety of contexts that are absolutely essential to their futures as citizens in a world that is becoming increasingly networked.

2) Human beings learn everything by interacting with, and acting on, their world. To do this, we use all of our sensory faculties — we hear, we see, we touch, we manipulate, we smell. Increasingly, we understand learning as an embodied experience — so that what our bodies do, how they are oriented in space, and how they interact with the context of our learning or activity, is now understood to matter quite a lot. The tools we use, the places in which we use them, and the feelings and senses we have as we use these tools in context are all inextricably connected to the thinking and learning we do. Scholars like Andy Clark, Arthur Glenberg, and Kevin Leander have helped us to understand the ways that learning and literacies are, in fact, embodied. This is the theoretical foundation for the gesture approach to L2 learning championed by Wendy Maxwell http://aimlanguagelearning.com

Okay — so given this, we must also acknowledge that we process and manipulate information in our brains. The extent to which we integrate the information that reaches our brains depends on a lot of factors — but to address the factors related to your colleagues’ assertions about the importance of writing with pens/pencils vs. typing — I can say that there is probably some truth in their observations because writing with pens/pencils engages multiple sensory channels. And, the more channels are engaged, the more information is coming in to our brains to be processed. So, writing involves holding a pen, moving it in certain ways to produce letters that are then seen/read. Some students might even say the words aloud as they write them — so there are two more modalities engaged — the ears and the voice.

3) Moreover, for young learners, the written page is a defined space that is clear of distraction. And, for cognitively demanding work — like learning another language — we know that distractions reduce our ability to attend to important details. The more we have going on in our environment (i.e., on the Internet) the more our attention will be divided. So, the observations that your colleagues have made may be as much about creating an optimal environment for undivided attention as anything.

4) I would say to your colleagues that they should not think of online vs. print-based literacies (L1 or L2) as being in tension or in opposition with one another. Rather, given the importance of digital literacies, we should think about providing students with a range of opportunities to develop all of the necessary literacies skills/mindsets/dispositions that will enable them to be fully engaged global citizens.It’s not a question of one context being better for learning than another. Rather, it’s about understanding the multiple contexts that our students will need to navigate and ensuring that they’re ready to do that. If anyone can help our students to do this — it’s the Modern/Foreign Language teachers. These are the colleagues who understand culture, who understand the complexities and multiplicities of meaning, who think in multiple sign systems all day, every day. In fact, I believe that the Foreign Language classroom is precisely where kids gain an understanding of the ways that meaning can be communicated that translate, actually, to the multimodal environments they meet online. Foreign language teachers have always, for instance, helped students to leverage images in ways that support meaning. Online, that’s an absolutely necessary skill because there are so many visual cues that communicate meaning.

References I shared:

Castañeda, D.A. & Cho, M-H.(2013).The role of wiki writing in learning Spanish grammar. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 26(4), 334-349. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.6

Kern, R. (2014). Technology as pharmakon: The promise and perils of the Internet for foreign language education. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 340-357. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4781.2014.12065.x

0026-7902/14/340–357

I also recommended that these colleagues regularly consult The Reading Teacher, The Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, The Modern Language Journal and Computer Assisted Language Learning for research findings to inform their work.

Photo reference: Wilke, S. (2009). Black and white icon of a question mark. Retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Icon-round-Question_mark.jpg. Used under author licensing to reuse the image “for any purpose without conditions”.

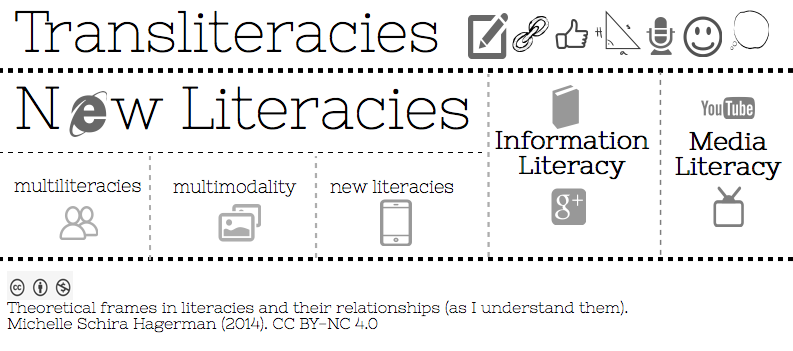

]]> This week, I’m presenting at a two-day workshop for the Association of Independent School Librarians. The title of the PD session is “At the Center of IT All: Scaffolding Advanced Information Literacies for K-12 Students in School Libraries”. One of the questions that the AISL wanted to explore through this PD session is one that many literacies scholars grapple with daily — how do theoretical frames such as transliteracies, New Literacies, multiliteracies, media literacy, and information literacy fit together? And to follow up on that question — how are these theoretical frames both similar and different?

This week, I’m presenting at a two-day workshop for the Association of Independent School Librarians. The title of the PD session is “At the Center of IT All: Scaffolding Advanced Information Literacies for K-12 Students in School Libraries”. One of the questions that the AISL wanted to explore through this PD session is one that many literacies scholars grapple with daily — how do theoretical frames such as transliteracies, New Literacies, multiliteracies, media literacy, and information literacy fit together? And to follow up on that question — how are these theoretical frames both similar and different?

In preparation for this talk, I’ve developed an infographic that will accompany more thorough exploration of these theoretical frameworks. I’ll share the full presentation once it’s finished, but for now, here’s a multimodal conception of the relationships between theoretical perspectives on literacies in a globally networked world. Notice that lines separating perspectives are permeable. Icons have been selected to represent elements of each theory that can be used to differentiate them from one another. Importantly, all of these perspectives include social, cultural and critical perspectives as fundamental literacies. Certainly, some theoretical frameworks have been left out and others may view the relationships among these perspectives differently. I’d love to hear your thoughts.

]]>Roughly, the story goes like this. We start with a comprehender who has specific goals, a given background of knowledge and experience, and a given perceptual situation. The perceptual situation may, for instance, be the printed words on a page of text. […] Given these idea units in the form of propositions as well as the reader’s goals, associated elements from the reader’s long-term memory (knowledge, experience) are retrieved to form an interrelated network together with the already existing perceptual elements. Because this retrieval is entirely a bottom-up process, unguided by the larger discourse context, the nascent network will contain both relevant and irrelevant items. Spreading activation around this network until the pattern of activation stabilizes works as a constraint-satisfaction process, selectively activating those elements that fit together or are somehow related and deactivating the rest. Hence, the name of the theory, the construction-integration (CI) theory: A context-insensitive construction processes is followed by a constraint-satisfaction, or integration, process that yeilds if all goes well, an orderly mental structure out of initial chaos.

Upon first reading this paragraph, the last sentence really struck a chord with me. Online, the magnitude of “chaos” presented by “the perceptual situation” can overwhelm readers – especially novices. I recognized that any teaching intervention that would help students make “an orderly mental structure” would have to help them stay focused on their purpose, and on what they already knew so that the process of ‘selective activation’ might actually occur.

I also decided that to build a network, it might be helpful for students to actually see its foundations as it grew. We know that background knowledge is a huge determinant of reading comprehension (Anderson & Pearson, 1984; Langer, 1984) but I hypothesized that if students could record what they already knew on their topic of inquiry (e.g., the pros and cons of nuclear power or whether a person with cancer should accept the risks of radiation therapy) AND be able to refer to it and build from it as they read across multiple texts, it might help them to solidify their understanding more effectively. I saw limitations, however, to regular paper.

If students took notes on a regular piece of paper, I worried that the background knowledge that they started with would be forgotten at the top of the page, or quickly muddled with what they had read. Plus, from a research perspective, I wanted to be able to see what students learned. The background knowledge had to remain, visually, as the foundation of the model students were building — and for that to happen, I needed students to be able to build up from it — to deliberately construct a layered model of understanding. As my advisor, Doug Hartman said, I needed to be able to separate students’ background knowledge from what they read just as maps allow geographers to see layers of topography.

So, what did I do? Well, I repurposed an old-school technology

Before doing any reading on the Internet, students in the treatment condition were asked to brainstorm, with their reading partner, everything they knew on the topic. Using a single color (which they chose from a rainbow assortment of permanent Sharpies) they jotted down their knowledge and related experiences on a single transparency sheet.

Yup. A good old sheet of 3M Transparency film. A few kids had never seen or touched the stuff. Most of them remembered it from “like, 2nd grade, before the digital projectors were installed”.

Then, when they began to read, students layered a second transparency sheet on top of the first. Students were told to build from their background knowledge, and to jot down important ideas from what they read using any method. The intervention also explicitly taught students to compare and connect new information to background knowledge. The transparencies allowed students to see their background knowledge — but it was also made old and new information physically separate entities that could be teased apart and then re-aligned.

In an informal interview, one student,who has completed the study, told me that having his background knowledge on the first transparency film allowed him to stay focused on the task purpose because seeing what he already knew reminded him of what he needed to find out.

I’ll be analyzing more data to determine the impact of the intervention overall, but based on my observations of students’ use of the transparency film, I think this method offers great promise to students as they construct “an orderly mental structure out of initial chaos” (Kintsch, 1998, p. 5). It’s simple, inexpensive, and it makes the process of building a mental model much more concrete for students and teachers alike. At any point in the reading inquiry process, everyone has access to where students started, and what they’ve since read and identified as important. Plus, it’s something that teachers across all subject areas can do — from K-12 — as they help students to integrate what they learn from multiple sources.

References

Anderson, R.C. & Pearson, P.D. (1984). A schema-theoretic view of basic processes in reading comprehension. In P.D. Pearson, R. Barr, M.L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 255-292). New York: Longman.

Kintsch, W., (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Langer, J. A. (1984). Examining background knowledge and text comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 19, 468-481.

]]>The chapter is useful, particularly for its closely juxtaposed definitions of Multiliteracies (The New London Group, 1996); New Literacies (Leu, 2002); Information Literacy (Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000); Media Literacy (Aufderheide, 1993); and Visual Literacy (Wileman, 1993; Stokes, 2001).This is an important contribution in its own right and I recommend it as a resource for students and scholars looking for a primer on the many perspectives that are emerging in this field (see pages 156-157).

The authors also take on the formidable task of describing the characteristics of 21st century literacies (p. 157-158) which, I’m guessing, probably felt much like pinning Jell-O to a wall, as they wrote their chapter. Given that the literacy landscape of the Internet is constantly changing — each year brings new tools, new skills, new learners with new experiences living in cultures around the world that are newly and differently affected by the Internet and its affordances — I appreciate that Rhodes & Robnolt had to draw a line in the sand and describe the landscape as they saw it in 2009. I agree with their assertions that “youth must adapt to working in multilayered environments” (p. 157) and be able to “transcend the linear, bounded and fixed qualities of written text” (p. 157) (also see Landow & Delaney, 1991, p. 3). I agree that twenty-first century literacy is characterized by multimodality, and that hypertext affords a reading experience that is multilinear.

I take issue, however, with their description of twenty-first century students. To me, the descriptions are too simplistic and they seem to advance a certain folklore about digital natives — that is, that they know more than most adults about technology and how to use it. Their description is grounded in the work of Mark Prensky — a great visionary thinker — but whose ideas, as paraphrased in this chapter, belie the true complexity of adolescent development and its interactions with technology, school and the caring adults who teach them each day.

Rhodes and Robnolt, paraphrasing Prensky (2006) say that “students today are becoming less engaged in old-style instruction that ignores the digital skills they bring to the classroom and enraged with teachers who are not re-creating curricula and instructions to meet their needs.” (p. 158) Really? I don’t deny that students’ out-of-school literacy practices are important and that they shape their hopes for in-school literacy activities. In the 1980s, I was thrilled when I got to watch TV in class! It’s what I liked to do at home! I take issue, however with the implicit messages in this quote — first, that “old-style instruction” is out-moded; second that because students engage with computer technologies (i.e, Facebook) at home that their learning needs are categorically different than they used to be; and third that teachers should be primarily designing their curricula to make their adolescent students “happy”.

To be clear, I’m a constructivist at heart. I believe in authentic, inquiry-based instruction that inspires creativity and problem solving. I believe that technology can be used to support this kind of learning — but I don’t believe that digital skills are necessary for deep learning to happen — even for digital natives. In fact, I would argue that school could just be the one place where kids are challenged to learn to think without technology too. If we want to encourage flexible thinkers, we need for digital natives to experience learning in different ways, with different tools and for different goals.

I support technology integration in every classroom, but only when it’s the best pedagogical choice. Prensky, Rhodes and Robnolt, it seems, are advocating technology use in schools because kids like it and they’re used to it. It seems to me this is the same argument that has been used to justify the selling of fried food, soft drinks and cookies in school cafeterias. Salad doesn’t sell. Kids want chips. To grow up healthy and strong, however, kids need to eat their vegetables. Old-school content, taught using old-school methods is not a categorically bad thing. I favour responsive, creative and inspiriational teaching, and I don’t know any student who would be “enraged” by a teacher who created this kind of learning atmosphere but without the use of technology. I think the spirit of being more responsive to students’ learning needs is laudable — but I am wary of recommendations and assumptions that emphasize digitality over the thoughtful consideration of the range of tools and practices that best support student learning.

Most kids already know how to social network and download music. What they need, in my view, are advanced new literacies skills that will permit them to “successfully exploit the rapidly changing information and communications technologies that continuously emerge in our world” (Leu, 2002, p. 13; Rhodes & Robnolt, 2009, p. 156). Rhodes and Robnolt, I think, would agree with me here. In my own research, I have observed that even the savviest digital natives are bad at this. Developmentally, kids aren’t different than they used to be in this regard. They still need caring adults to scaffold their cognitive growth by providing rich and diverse learning experiences that include — and do not include — digital media.

References

Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000). Information literacy: Competency standards for higher education. Chicago: American Library Association.

Aufderheide, P. (1993). Media literacy: A report of the national leadership conference on media literacy. Queenstown, MD: Aspen institute. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 365 294).

Landow, G.P. & Delaney, P. (1991). Hypertext, hypermedia, and literary studies. The state of the art. In P. Delaney & G.P. Landow, (Eds.) Hypermedia and literacy studies (pp. 3-50). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Leu, D.J., (2002). The new literacies: Research on reading instruction with the Internet. In A.E. Farstrup & S.J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 310-336). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies: Designing social futures. Harvard Educational Review, 66(1), 60-91.

Prensky, M. (2006). “Engage me or enrage me” : What today’s learners demand. Educause Review, 40(5), 60-64.

Stokes, S. (2001). Visual literacy in teaching and learning: A literature perspective. Electronic Journal for the Integration of Technology in Education. Retrieved from http://ejite.isu.edu/Volume1No1/Stokes.html

Wileman, R.E. (1993). Visual communicating. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

]]> Last week in my adolescent literacy development seminar, we discussed issues and literature related to family literacies. Toward the end of class, our professor, Doug Hartman, cited a landmark study by Victoria Purcell-Gates ( at UBC in Language and Literacy Education where I completed my M.A.) that focused on three kinds of texts in the home: trade books, coupons and the TV guide (citation below). Once, not that long ago, Doug recounted that he asked Dr. Purcell-Gates what the most significant texts in the home might be today and how those texts might shape family literacies differently. Though Dr. Purcell-Gates didn’t apparently have an immediate reply to the question, my colleagues and I took it up ourselves. With Doug’s prompting, we also expanded our discussions to consider how digital tools are shaping family literacies. Though speculative and grounded in personal experiences, these are my thoughts.

Last week in my adolescent literacy development seminar, we discussed issues and literature related to family literacies. Toward the end of class, our professor, Doug Hartman, cited a landmark study by Victoria Purcell-Gates ( at UBC in Language and Literacy Education where I completed my M.A.) that focused on three kinds of texts in the home: trade books, coupons and the TV guide (citation below). Once, not that long ago, Doug recounted that he asked Dr. Purcell-Gates what the most significant texts in the home might be today and how those texts might shape family literacies differently. Though Dr. Purcell-Gates didn’t apparently have an immediate reply to the question, my colleagues and I took it up ourselves. With Doug’s prompting, we also expanded our discussions to consider how digital tools are shaping family literacies. Though speculative and grounded in personal experiences, these are my thoughts.

The single most significant and immediately obvious contribution that digital tools make to my family’s literacy practices is access to ideas. When my 5-year-old wanted to know how many venomous snakes there are in the world, we Googled her question. Turns out, there are over 600 (thank you, Wikipedia). We found facts, images and videos that captivated her imagination for weeks. When she wanted to know what a mummy was, we did the same thing. We discovered plenty of information about Ancient Egyptian burial, but we also learned about the excavation of mummies in China. It’s stunning to think that in seconds, my daughter can explore answers to every question she can imagine.

It seems that my daughter’s reading comprehension should never be limited by her background knowledge; she has immediate access to answers, and she knows it. “If you don’t know something, Mom, you should just go to the Internet,” she informed me, yesterday. The Internet certainly has a prominent place in our family literacy practices. As we use it, I’m increasingly aware that my husband and I are scaffolding basic new literacies skills like questioning, locating and evaluating what we find too. I wonder how other families use the Internet with their young children?

I also wonder how my daughter’s iPod Touch is shaping her notions of text. Certainly, we have shelves of storybooks in our home as did the participants in Purcell-Gates’ study. We cherish our books but we also read digital stories with interactive characters that ask my daughter questions and with images that leap off the page. With a tap, she can also navigate to her music collection, or play the drums, or win points in a math game, or draw a picture or pretend to be a Jedi in a light-sabre duel with her dad. I wonder what the synergy of literacy, numeracy, art and entertainment in this tiny box will mean for her developing notions of literacy. Will these activities all seem different or more similar to her because they all live in her hand-held device?

Purcell-Gates, V. (1996). Stories, coupons, and the TV guide: Relationships between home literacy experiences and emergent literacy knowledge. Reading Research Quarterly, 31(4), 406-428. doi:10.1598/RRQ.31.4.4

]]>